Vagus - the Great Wandering Nerve

Yogis, mystics and natural healers have long known that mind and body cannot be separated and treated as two separate entities. Advances in neuroscience and related fields are bringing new evidence and frameworks to our understanding of the mind-body connection. Consequently, treatments for mental health issues continue to integrate awareness of the body and an understanding of physiological factors that influence mental and emotional well-being. This post is the first in a series exploring physiology and mental health.

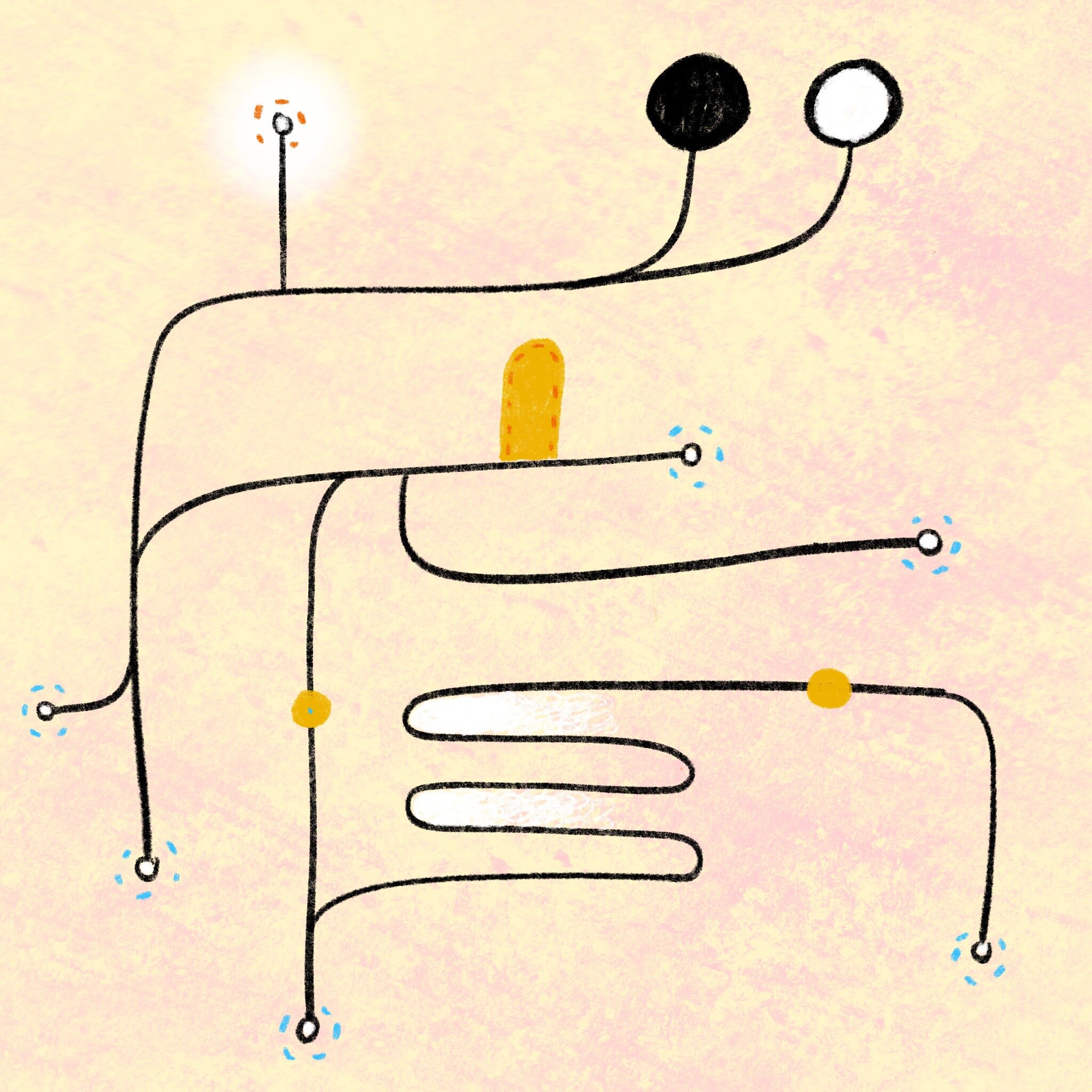

Starting at the back of our heads and extending down into our bellies through many wandering pathways is the vagus nerve. The vagus (from the latin for wander), is the tenth cranial nerve. Images of the nerve show two paths in the brainstem and cerebellum that branch out into many vital organs, passing through the heart and lungs, settling deep into the abdomen, and facilitating bidirectional communication between the organs and the brain.

Just take a moment to consider and feel in your own body all of the places that the vagus travels. Imagine these nerve pathways moving information both up and down in a complex, bidirectional flow of communication.

The vagus nerve plays a role in the regulation of many bodily functions, including digestion, heart rate and immunity, and has both sensory and motor functions. About 10-20% of the vagus nerve fibers send signals down from brain to organs, helping to stimulate muscles that regulate heart rate, move food through the digestive track and mediate anti-inflammatory responses, among other tasks. Another 80-90% of fibers bring “information of the inner organs, such as gut, liver, heart and lungs to the brain. This suggests that the inner organs are major sources of sensory information to the brain…” (Breit, Kupferberg, Rogler & Hasler, 2018).

Sensory communication through the vagus nerve also reaches areas of the ear, throat, and tongue. The vagal pathways that send information up to the brain from the organs are involved in the activation and regulation of the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, which plays a key role in the regulation of stress. The vagus nerve can be damaged, or become impaired in its function, due to stress and other biological or environmental factors. Impaired functioning of the vagus nerve can impact many body systems, affecting mood and emotions.

As primary regulator of the parasympathetic nervous system, healthy vagus nerve function plays a central role in the regulation of heart rate, blood pressure and organ function, acting as a physiological break, slowing down body functions so that we can rest, digest and relax, and also conserving energy in the face of threat. Steven Porges’ Polyvagal Theory offers a deeper understanding of the ways the vagus nerve functions to support well-being.